『工芸青花』14号

■2020年6月10日刊

■A4判|麻布張り上製本|見返し和紙(楮紙)

■カラー160頁|望月通陽の型染絵を貼付したページあり

■限定1000部|10,000円+税

■御購入はこちらから

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=393

Kogei Seika vol.14

■Published in 2020 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■160 Colour Plates, Frontispiece with a stencil dyed art work by Michiaki Mochizuki

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary and all photographs are with captions in English

■Limited edition of 1000

■10,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=393

目次 Contents

1 北京の工芸

The Craft in Beijing

・胡同の文人 齋藤希史

・中国・現代・生活工芸 安藤雅信

・「文人」とはなにか 閑野譚

・一〇〇年前の北京と古美術 川島公之

・彼我のことなり 舟橋昌美

2 川瀬敏郎の花 大徳寺孤篷庵

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Koho-an, Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto

・シンをたてる 川瀬敏郎

3 メキシコのブリキ絵 芹沢銈介コレクション

Mexican Retablos from Keisuke Serizawa Collection

・対話の気配 高木崇雄

・キリスト教の奉納画 金沢百枝

連載 Series

・ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群8 堀江敏幸

扉の絵

精華抄

扉の絵 4

The Frontispiece 4

望月通陽《蕩児の帰宅》 2020年 型染

父の遺した彫刻刀を使って料理屋の看板など彫ることがある。小振りの引き出し数段に並んだ彫刻刀はどれもが静かに研ぎ上げられ、薄く油も引かれ、父の亡きあと二十数年がたちながら、今でも働く気概を見せつけている。だから私の貧しい手技でも、わずかな力だけで仕事は流れるようにはこんでくれる。

しかし私は刃物を研ぐことが出来ない。研げばどれもがなまくらになり、そのたび父を一本ずつ失う気さえする。道具というひとつの愛すべき思想も生かせぬ私は無駄口の多い拗ね者になった。群れず属さず、時流にも取りこまれず、黙々と彫刻刀を研ぎ上げて逝った父を、蕩児は今更ながら潔ぎよしと思う。(望月通陽/染色家)

Michiaki Mochizuki, The Return of the Prodigal Son, 2020, Katazome (Japanese stencil print)

Occasionally, I carve a fascia board for a restaurant, using the carving tools of my father. They are neatly placed in a few racks of small drawers, are serenely whetted, guarded from rust by thin coat of oil, and even after twenty years or so from my father’s death, are still very willing to work. Because of my poor skill, I would not think of carving a fascia without the help of these sharpened tools. It needs just a push to finish the work, moving naturally like a water flow.

But I cannot whet the tools. If I do, every blade will become dull. Every time one gets dull, I feel as though I lose my father once and again. The son who cannot make the best of his father’s tools, the beloved ideology, became a cynic with an idle talk. He never herded together, never belonged to an establishment, and never thought of swimming with the trend, but he always whetted the tools quietly, until he passed away. After such a long time, the prodigal son is proud of such father. (Michiaki Mochizuki / Artist)

1|北京の工芸

The Craft in Beijing

昨年四月、陶芸家でギャルリももぐさ代表でもある安藤雅信さん(一九五七年生れ)と、北京を取材しました。主題は工芸で、対象は人でした。詳しくは安藤さんの本文に書かれていますが、近年、北京にかぎらず東アジアで日本のいわゆる「生活工芸」文化がひろく受容されつつあり、安藤さんはその代表作家として、頻繁に彼地で個展、茶会(中国茶)をおこなっています。

人選は安藤さんによります。多くの人と話しましたが、この記事で紹介するのは七名。黄永松(編集者。一九四三年生れ)、王峰(陶芸家。一九七二年生れ)、李曙韻(茶人。一九六九年生れ)、白昀澤(骨董商。一九八八年生れ)、徐漠(金工家。一九六八年生れ)、李若帆(工芸店主。一九七二年生れ)、馬可(衣服デザイナー。一九七一年生れ)の各氏です。意外なことに、北京生れはいませんでした。話していてつよく感じたのは、ああこの人たちのよりどころは足もとにあるんだな、ということでした。たとえば老荘、孔孟、唐宋明代の文人文化などです。そうした連続性、内発性は日本文化もかつては(大陸とはことなるかたちで)有していたはずですが、戦後急速にうしなわれました。かわりのよりどころはあるのでしょうか。

一九九〇年代にはじまるとされる「生活工芸」は、「生活」をよりどころにする(しようとする)文化運動でした。北京で気づいたことのひとつに、「文人」とは、抵抗的精神にもとづく「生活の芸術化」ではないのか、ということがあります(そのようにみえました)。私たちは、遠くないのだと思います。S

Last April, I visited Beijing with Masanobu Ando (born in 1957), a ceramic artist and an owner of Galerie Momogusa, in Gifu. The theme was the craft, and the object was the person. In recent years, not only in Beijing but also in East Asia, the so-called ‘Craft for daily life’ culture of Japan has been gaining broad acceptance. As a representative artist, Ando frequently holds solo exhibitions and tea parties (Chinese tea) in China.

Ando chose whom to see. We met many, but I chose seven for this article. Huang YongSong (an editor, born in 1943), Wang Feng (a ceramist, born in 1972), Li ShuYun (Chinese tea master, born in 1969), Bai YunZe (an antique dealer, born in 1988), Xu Mo (a metalwork artist, born in 1968), Li RuoFan (an owner of the craft shop, born in 1972), and Ma Ke (a fashion designer, born in 1971) is the seven. Surprisingly, not one of them was born in Beijing. What I felt very strongly as we talked was that these people’s strength lies in their feet. For example, their spiritual foundation is the philosophy of LaoZi and ZhuangZi, the teachings of Confucius and Mencius, and the literary culture of Tang, Song, and Ming dynasty. Such continuity and indigenousness should have been present in Japanese culture in the past (perhaps in a different way to China), but it was quickly overtaken after the WW2. Is there a substitute for it?

The ‘Craft for daily life’, said to have begun in the 1990s, was a cultural movement that attempted to place ‘daily life’ at its core. One of the things I noticed in Beijing was that ‘literati’ are not (or seemed to be) the ‘a kind of ‘Art’-ification of daily life’ based on a spirit of resistance. We are not far away. (S)

2|川瀬敏郎の花 大徳寺孤篷庵

Flowers by Toshiro Kawase at Koho-an, Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto

花人の川瀬敏郎さん(一九四八年生れ)の花、今回は京都の大徳寺孤篷庵における「たてはな」です。

たてはなとは室町期に大成した様式で、芸能としてのいけばなの源流にあたるものです。〈山から伐り出した常盤木を浄め、稲藁を選り、さらに蒿の芯を抜き出して束ねて込み(花留)とし、瓶に仕込んで水を張る。居住いを正して心を鎮め、天地を見定め、常盤木を拝して両手で高く持ち上げ、地球の根元に突き立てる気迫をもって込みの真中に垂直にたてると、瓶上に「カミ」が立ち現れ、常盤木は「シン」になる〉(川瀬敏郎)

たてはなとはなにかという問いは、なげいれの花とともに、川瀬さんにとって終生のものです(今年刊行予定の本『花をたてる』は、『芸術新潮』で六年にわたって連載した記事を増補したもので、川瀬さんのたてはなの集大成になるはずです)。〈一木一草一花をたてることは、カミの肖像を描くことである。シンをたてることが、いけるやいれるとは異なり、格別な聖性をもつのは、たてるという行為が、カミを奉る太古の神事を体現しているからで、時間にすれば数秒とないが、私はこの間、間違いなく始源に立ち返る〉(同)

臨済宗(禅宗)大徳寺の塔頭孤篷庵は、小堀遠州(一五七九—一六四七)が寛永二〇年(一六四三)に龍光院より移し(拡張し)造立した寺。寛政五年(一七九三)焼失するも、その後数年内に松平不昧(一七五一—一八一八)らの尽力で再興されました。茶室(一二畳)は起し絵図などにより忠実に再現、書院(八畳。次の間六畳)は創建時とややことなり、茶室(四畳半台目)は再建時に直入軒に附設されました(いずれも重文)。S

The flowers of Toshiro Kawase (Ikebana artist, born in 1948) were arranged as Tatehana in the hermitage Koho-an in Daitokuji Temple in Kyoto.

Tatehana (the vertical flower arrangement) is a style that was established in the Muromachi-period and is the origin of Ikebana as an art form. Purify the branch of an evergreen tree cut from the mountains, select rice straw, pull out the core of the mugwort and bundle it as a peg. Put it in a vase and fill it with water. You must correct attitude, calm your mind, discern the heavens and the earth, and then, raise the branch vertically with both hands and push it in the middle of the peg with all the might as if to thrust it to the root of the earth. Then ‘Kami’, a god will appear from the vase, and the straight evergreen branch will become the core (‘Shin’). By Toshiro Kawase.

The question of what is a Tatehana is a lifelong question for Kawase, as is the flower of Nageire (throwing in style). (His book, To arrange Tatehana, coming up later this year, is going to be a compilation of his concept of Tatehana, which is an expanded version of the articles he wrote in Geijutsu Shincho over the six years.

‘To make a tree, a grass, and a flower into an arrangement is like making a portrait of Kami. To build the core (‘Shin’) is different from the act of arrangement and throw in and it has a special holiness to it because the action of verticality is the embodiment of ancient ritual of venerating Kami the god. It is not a few seconds in time, but at this moment, I return to the primordial beginning.’

Koho-an within Daitokuji Temple of Zen Buddhism is a hermitage which Kobori Enshu (1579-1647) relocated and expanded from Ryuko Temple in 1643. After the fire in 1793, within a few years, it was rebuilt with the efforts of Matsudaira Fumai (1751-1818) and others. The teahouse Bosen was faithfully reconstructed from the three-dimensional plan of the original building. The drawing-room Jikinyuken is a little different from the original. The teahouse Sanunjo was attached to Jikinyuken. (S)

3|メキシコのブリキ絵 芹沢銈介コレクション

Mexican Retablos from Keisuke Serizawa Collection

〈メキシコを工藝がまだ生きている国として好んだゆえでしょうか、池田三四郎など、古くから民藝運動に関わった人々のうちに、時折ブリキ絵を所蔵している方を見かけます。その中でもとくにブリキ絵を好み、また僕の知る限りにおいて、メキシコのブリキ絵を日本国内でもっとも蒐集したのは、芹沢銈介です〉(高木崇雄)

染色家の芹沢銈介(一八九五—一九八四)は静岡県生れ、東京高等工業学校図案科卒業後、柳宗悦(一八八九—一九六一)と沖縄の紅型を知り、工芸の道、型染の道へすすみます。その仕事の大略は生前に建てられた静岡市立芹沢銈介美術館(白井晟一設計)でみることができます。芹沢は大収集家でもあり、館では彼があつめた世界の工芸品約四五〇〇点を収蔵、展示しています。古道具坂田の坂田和實さんはかつて芹沢邸へエチオピアの十字架など持参した日のことを回想し、〈帰り道は嬉しかった。この人を目標とし、この人をウッと唸らせる品物を集めようと心に決めた〉と書いています(『ひとりよがりのものさし』)。

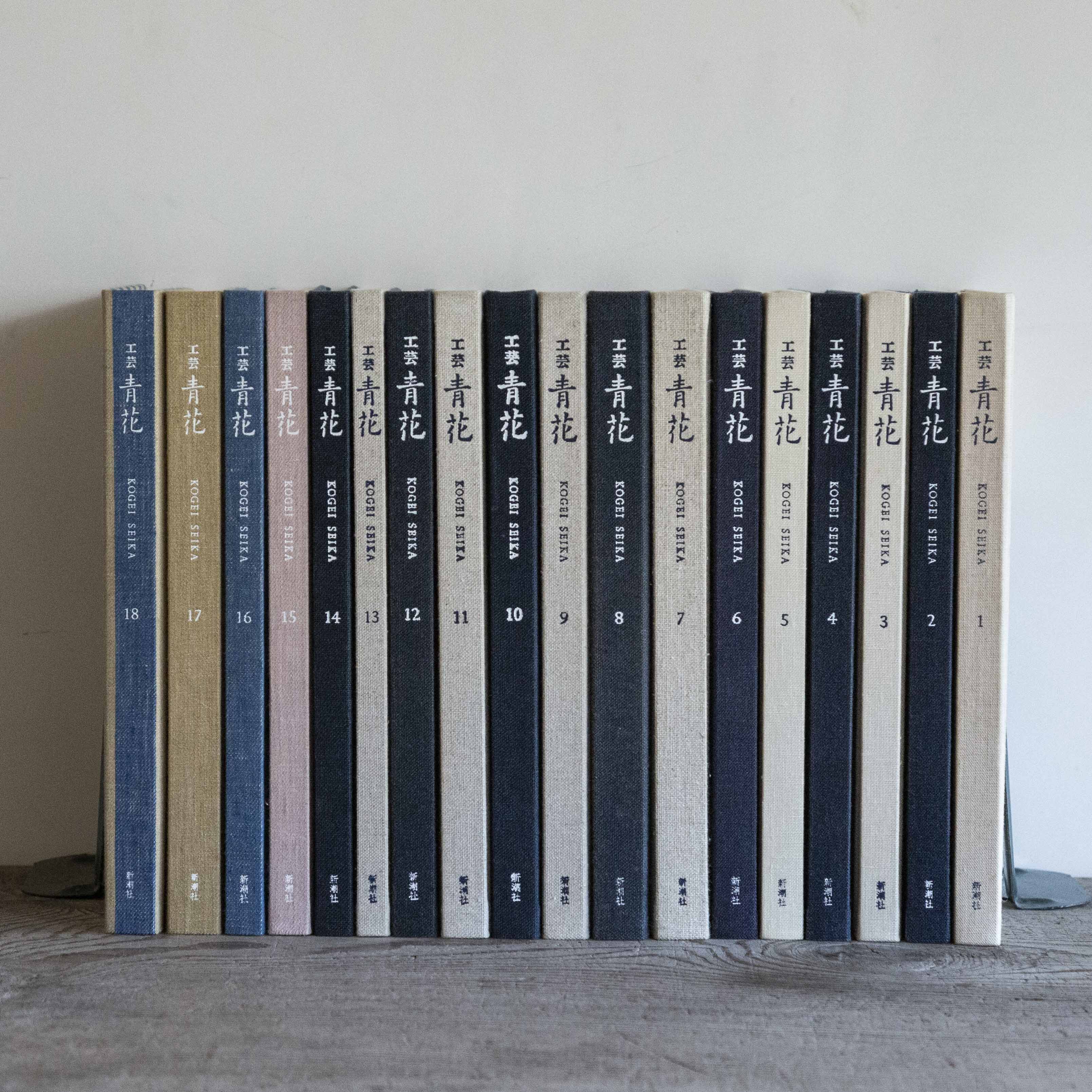

メキシコのブリキ絵は『工芸青花』二号でも特集しました。そのときは高木さんの収集品と文章でした。〈使い古しの小さなブリキ板にペンキで記されたこれらの奉納画を、芹沢銈介にならってブリキ絵と呼んでいるけれど、メキシコではEx-voto(奉納画)ともRetablo(祭壇画)とも呼ばれている。(略)ブリキ絵には必ず聖人が描かれ、その聖人のとりなしによって叶えられた、暮らしの中のささやかな、時に大きな喜びの姿とその詳細を記した言葉が描きこまれている〉〈必ずしもブリキだけではなく、布地や木、合板などに描かれることもある。また、ブリキ絵描きという職業は、のちになって専門職として分化したが、誕生当初は教会において同様の仕事を担当していた者や、近隣の印刷を生業とする者が作成を請け負っていた〉

今回は、芹沢銈介収集のブリキ絵全一八点を、東京蒲田から静岡に移築された芹沢旧邸内で撮影、掲載しました。S

Perhaps because Mexico is a country where crafts are still alive, people involved in the Mingei movement (Craft movement in Japan) was fond of the country. Many, such as Sanshiro Ikeda, own tinplate paintings from Mexico. Among them, Keisuke Serizawa has a particular preference for tinplate paintings, and to my knowledge, and was the largest collector of Mexican tinplate paintings in Japan. By Takao Takaki.

Keisuke Serizawa (1895-1984), was a textile-dyeing artist, born in Shizuoka Prefecture. After graduating from the Design Department of the Tokyo High School of Technology, learned about Okinawan red stencils with Muneyoshi Yanagi (1889-1961), and proceeded on the path of craft and stencil dyeing. A summary of the work can be seen at the Shizuoka City Serizawa Keisuke Art Museum, designed by a Japanese architect, Seiichi Shirai. Serizawa collected crafts from all over the world, and the museum houses and displays about 4500 from his collection. Kazumi Sakata of the Antique Sakata reminisces about the day when he brought Ethiopian crosses and other items to the Serizawa residence. ‘I was happy on the way home. I made up my mind to make him an aim and collect items that would make him gasp ooh and aah,’ writes Sakata in his book, My Own Yardstick (2003).

In the second issue of Kogei Seika (2015), we featured tinplate paintings from Mexico. The article was on Takaki’s ex-voto collection. He writes that ‘I call these ex-voto paintings as ‘tinplate paintings’ after Keisuke Serizawa, but in Mexico, there are two different categories, i.e., the painted ex-voto and retablo. (…) The saints must be there on painted ex-voto, for the miracles (mostly trivial and sometimes significant) explained with the words and depictions in detail are realized by their intercession.’ ‘The tinplates are not the only media used for ex-voto. Fabric, wood, or plywood is also appropriate. The artisans in the church and those in the printing business of the neighbourhood initially undertook painting the ex-votos. The profession as ex-voto painters only established later in history.’

In this issue, we photographed all eighteen of Serizawa’s tinplate paintings in the old residence, which was relocated from Kamata in Tokyo to Shizuoka. (S)