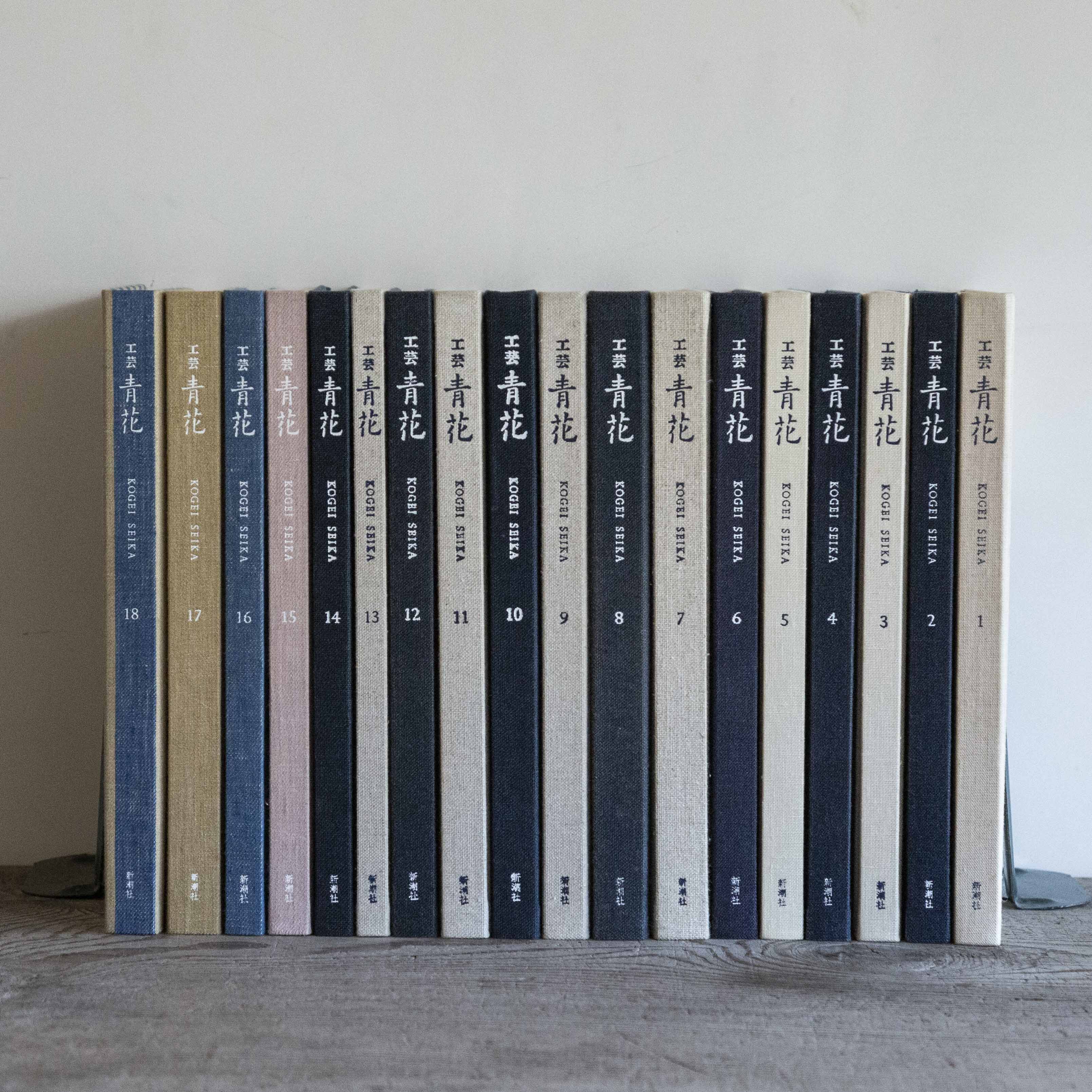

『工芸青花』11号

■2019年2月25日刊

■A4判|麻布張り上製本|見返し和紙(楮紙)

■カラー192頁|望月通陽の型染絵を貼付したページあり

■限定1200部|12,000円+税

■御購入はこちらから

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=273

Kogei Seika vol.11

■Published in 2019 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■192 Colour Plates, Frontispiece with a stencil dyed art work by Michiaki Mochizuki

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary

■Limited edition of 1200

■12,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=273

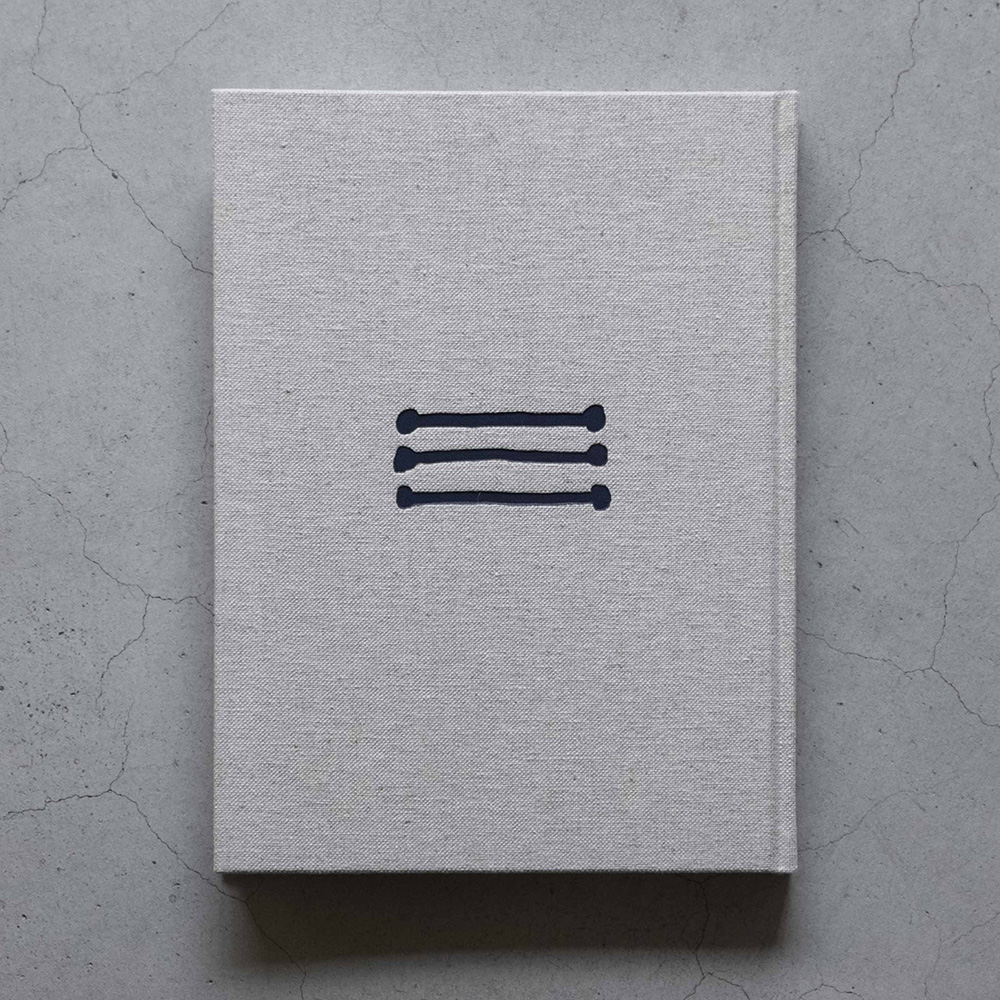

扉の絵 1

The Frontispiece 1

望月通陽《不安な怪物》 2018年 型染

碾いたもち米と米ぬかをこねて型染めの糊を作る。この割合の加減で染め上がる絵の表情が変わる。もち米が多くやわらかであれば、絵は縁にまるみを帯びておだやかになり、逆に米ぬかを増やしてねばりを減らすと、絵は縁を際立たせてにわかにきびしい表情になる。さて今回染めたこの奇妙な動物も、もう少し米ぬかの多い糊であったなら、こんなに長閑な姿ではなく、むしろ伝説の勇者に退治されるべく威厳ある怪物にさえなれた筈である。(望月通陽/染色家)

Michiaki Mochizuki ‘An Uneasy Monster’ 2018, Katazome (Japanese stencil print)

Glue for stencil dyeing is made from rice bran and powdered glutinous rice kneaded well together. The proportion of the two critically affects the expression of the ‘picture’. With more glutinous rice, the glue is softer, giving the picture a more placid feel with rounded outlines. On the contrary, more rice bran results in less adhesive glue, sharpening the edges of the picture with a stark impression.

So, if I had used glue with more rice bran, this peculiar animal in the current issue of Kogei-Seika would not have been of such an idyllic sort, but a monster so majestic to be subjugated by a legendary hero. (Michiaki Mochizuki / Artist)

目次 Contents

1 山茶碗

Yama-chawan

・石のようなもの─秦秀雄 勝見充男

・最初の古美術品 高木孝

・ざらざらしたもの 小澤實

・山茶碗入門 清水喜守

・深シ奥 枯レツレバ─柳宗悦 白土慎太郎

・茶道具として─北村謹次郎 木村宗慎

2 欧州タイル紀行

A Journey to the European Medieval Tiles

・アヴィニョン・教皇・ナポリ 金沢百枝

3 大谷哲也 「生活工芸」以後の器

Tetsuya Otani: Tableware in the Post-New Standard Crafts

・丸裸と白 富井貴志

4 川瀬敏郎 籠にいける

Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase: Flowers in Baskets

・消えた色気 片柳草生

5 骨董と私

On My Antique Collection

・藤末鎌初 杉村理

6 ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群 5

Fragments on Robert Coutelas 5

・髑髏の闇から抜け出て 堀江敏幸

7 名物とはなにか

What is Renowned Objects (Meibutsu) in tea utensils?

・「名物」批判にこたえる 木村宗慎

扉の絵

精華抄

1|山茶碗

Yama-chawan

山茶碗とはなにか。やきもの事典等の説明をさらにかいつまんでいうと、「東海地方の中世窯で平安後期(一一世紀後半)より生産された日常雑器。穴窯でかさね焼きされた無釉の碗で、口径一五糎、高さ五、六糎ほど。生産者は兼業(半農半陶)ではなく専従の小集団か。山茶碗の名は窯址のある山麓で陶片が出土することから。行基焼、藤四郎焼とも」。猿投、常滑、渥美ほか、おもな窯址(群)は四八頁の地図に記載しました。

〈名古屋市の東部に広がる丘陵地帯に分布する五〇〇基ほどの窯からなる猿投山西南麓古窯跡群(略して猿投窯)を始めとする古代の灰釉陶器窯は、中国陶磁の参入による中央権門との需給関係の悪化や中部・関東地方の農村地帯での日用雑器の需要増大に対応するために、十一世紀後半には施釉技法を放棄して無釉の山茶碗を主に生産する窯に転換していった。(略)知多半島の陶器生産も例外でなく、猿投窯の陶工が南下して常滑窯を形成したと考えられている〉(赤羽一郎「中世陶器の流通—常滑窯製品を追って」/網野善彦・石井進編『中世の風景を読む3—境界と鄙に生きる人々』より)

取材は山茶碗を愛する六人と、山茶碗を蔵するふたつの美術館でおこないました。掲載したのは二四碗。側面、見込、高台の写真はかならず載せて、通し番号を附しています。出自が雑器のせいか、一部(今回の六人のような)をのぞけば美術業界ではあまり評価されない山茶碗ですが、私は、内外とわず、もっとも好きなやきもののひとつです。S

What are the Mountain tea bowls (yama-chawan ware)? According to one dictionary, ‘they are simple tableware for everyday use, produced in medieval kilns in Tokai region (Pacific Ocean side of the centre of Honshu island) during Heian period (last half of the eleventh century). Unglazed bowls are pit fired in stacked piles and are roughly 15 cm in diameter and 5 to 6 cm in height. They seemed to be made by groups of professional potters, not by part-time farming households. The name ‘Mountain’ derives from the fact that the sherds are found in kilns in mountainous areas. They are sometimes called Gyokiyaki, or Toshiroyaki’. Major sites of the old kilns, such as Sanage, Tokoname, and Atsumi, are marked on the map in page 48.

‘The ancient production centres for ash glazed pottery, such as Sanage kilns at the south-western foot of the Sanage mountain (the site is made up of five hundreds kiln remains, scattered in the hilly area to the east of Nagoya), abandoned the technique of glazing in the last half of the eleventh century, after the decrease in demand of grand noble families due to the introduction of Chinese pottery and also after the increase in demand of tableware in rural areas of Chubu and Kanto regions (the central and eastern part of Honshu island), and they transformed themselves to the kilns producing unglazed ware like yama-chawan ware. (…) The pottery production in Chita peninsula also the case and it is assumed that the advance of the potters of Sanage to the south formed the kilns of Tokoname’ (Ichiro Akabane ‘The Circulation of Medieval Pottery; in search of Tokoname ware’ in Reading the Medieval Landscape 3, People living in the Boundary and Rural Society, edited by Yoshihiko Amino and Susumu Ishii).

I interviewed six people who admire yama-chawan, and photographs were taken in two museums which own them. There are 24 yama-chawan in this article. All with photographs of side views, inner views, and the views of the foot, numbered in serial. Perhaps because they were originally everyday tableware, not many antiquairians appreciate highly of yama-chawan except the particular few like the six whom I interviewed. For me, yama-chawan is one of the favourite ceramics. (S)

2|欧州タイル紀行

A Journey to the European Medieval Tiles

昨年の冬、ロマネスク美術(西欧一一—一二世紀)の研究者である金沢百枝さんから、一四世紀にフランスのアヴィニョンにあった教皇庁の舗床タイルの図録をみせてもらいました。白地に焦茶の線と緑釉でいろどられたそれは、動物文も抽象文ものびのびしていて心が晴れます。初期のマヨリカ焼に似ていて、均斉をおもんじる西洋美術史では傍流といえるロマネスク美術にもつうじる魅力です。ふしぎなのは、「国際ゴシック様式」のさきがけとされるアヴィニョン教皇庁の壁画は優美で宮廷趣味的で(つまり上手で)、タイルの文様とおよそ調和的でないことです。

今回の記事は昨年三月、金沢さんとアヴィニョンほかで取材したものです。教皇庁のタイルが近郊ユゼスで焼かれていたことなど、近年の研究成果も紹介しています。イタリアのオルヴィエートとヴィテルボをたずねたのは、「教皇」(ともに離宮がありました)と「マヨリカ焼」(どちらも産地でした)の線でアヴィニョンとつながり、タイルの源流をみいだせるだろうかと考えたからでした。S

Last winter, Momo Kanazawa, an art historian specialized in the Romanesque Art, showed me an exhibition catalogue of medieval pavement tiles excavated from the Popes’ Palace in Avignon, France; the most magnificent castle from the fourteenth century. On the white ground of the tiles, lines are drawn in dark brown and coloured by green glaze. The decorations are zoomorphic as well as geometric and the lines are so unconstrained that they made me so cheerful. They resemble the archaic maiolica in technique. They reminded me of the Romanesque art, the enfant terrible in the history of Western Art in the way that it is out of proportion and symmetry which the Western art values. The tiles adorn the rooms with fresco in International Gothic style. Why did they decide to pave these rustic tiles, while the frescos are courtly and sophisticated?

This article is based on the travel made in March 2018, with Momo. The article refers to the recent findings that the early tiles from Popes’ Palace were made in Uzege. With the hope of finding the origins, of the tiles of Avignon, we visited Orvieto and Viterbo, where there were also palaces of Pope, and produced maiolica. (S)

3|大谷哲也 「生活工芸」以後の器

Tetsuya Otani: Tableware in the Post-New Standard Crafts

前号で黒田泰蔵さんの白磁の記事をつくりました。この記事はその続篇といえます。大谷哲也さんは一九七一年神戸生れ、信楽に住まいと工房をかまえ、陶芸家の桃子夫人と娘さんたちと大きな犬と暮しています。助手はいません。大谷さんの器の特色は轆轤成形の白磁、定番式で(つまり同形同寸の器があり、替えがきく)、工業製品とみまがうほどに「手」のあとを消しています。後世に日本の食器の様式史(ただし手工芸史)が書かれるとして、この三〇年(一九九〇年代—二〇一〇年代)で特筆すべきことは「様式の無国籍化」と「白い(無地の)器の席捲」であり、そうした動向のさきがけが黒田泰蔵、継承したのがいわゆる生活工芸派の作家たち(赤木明登、安藤雅信、内田鋼一、辻和美、三谷龍二)です(いまはその時代はすぎつつあり、古典回帰や絵皿的器など、特筆すべきとはいいがたい、懐古趣味的、美術工芸的様式が多見されます)。

大谷さんの器は「黒田—生活工芸」の系譜上にありますが、大きなちがいは「手のあと」の有無です。黒田さんも生活工芸派の器にも、手仕事の結果としての「ゆらぎ」があり、それが現代の器作家がそうじてむきあわざるをえない工業製品の食器との差違であり価値になります(黒田—生活工芸の場合はかなり「ひかえめ」ですが)。大谷さんはそうした「ゆらぎ」にたいして禁欲的です。黒田—生活工芸と大谷さんの差違とは、つまり、前者が(ひかえめとはいえ)手工芸的手工芸なのにたいして、後者は工業製品的手工芸であることです(しかも作家主義的でありつつ)。

大谷さんのように自覚的に、懐古趣味におちいらずに「生活工芸以後」を生きている器作家は多くないと思います。今回の作家論(大谷さんはなにをやろうとしているのか)を、そのひとりである木工家の富井貴志さん(一九七六年生れ)にお願いしました。S

The previous issue featured an article on white porcelain by Taizo Kuroda, to which the present article is a sequel. Tetsuya Otani, born in Kobe in 1971, studied industrial design at an art university, and began pottery at the Ceramic Research Institute at Shigaraki, where he worked as a lecturer. Leaving the Institute, he stayed in Shigaraki, setting up a studio with his wife, Momoko, herself a potter, and living with their daughters and a big dog. They do not have assistants.

The characteristics of Otani are white porcelain produced through the wheel-throwing process, with regular shapes (each shape has its own numbering, thus replaceable), seemingly erasing traces of the ‘hand’ of the potter as if industrial products. If in the future a history of Japanese handcrafted tableware discusses the last thirty years (the 1990s to the 2010s) in terms of form criticism, it will pick up ‘the loss of country-specific features in form’ and ‘the prevalence of white (plain) vessels’ as worthy of special attention. A pioneer in these trends was Taizo Kuroda, who were followed by the artists of ‘New standard crafts’ (such as Akito Akagi, Masanobu Ando, Koichi Uchida, Kazumi Tsuji, and Ryuji Mitani), whose period is passing, and nostalgic styles returning with unremarkable result.

Otani’s tableware is in line with the ‘Kuroda-New-Standard-Crafts’ genealogy, but a major difference can be seen in ‘traces of the hand’. Crockery made by both Kuroda and new-standard-craft artists leave as a mark of handiwork ‘fluctuations’, which provides a difference and unique value to mass-produced products, however subtle their fluctuations are. Otani is more stoic towards this kind of ‘fluctuations’. While Kuroda-NSC artists represent, if in a modest way, the handicraft-handicraft, Otani represents the handicraft in the guise of industrial products.

There are only a few tableware potters who live the ‘post-new-standard-crafts period’ without falling into nostalgia for the past. I asked one of those few, Takashi Tomii (woodworker, born in 1976), to consider in this article what Otani has been trying to achieve. (S)

4|川瀬敏郎 籠にいける

Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase: Flowers in Baskets

前号は唐物籠でした。それは上手の、真行草でいえば「真」の花入です。今回は魚籠や農具など、「草」の籠。はじめから籠で二回と決っていました。花人の川瀬敏郎さんとは二〇年以上まえから、三桁をこえる回数の取材をしてきたので(月刊誌で連載をしているとおのずとそうなります)、川瀬さんにとって籠がどれほど大事か、桜が花の代名詞であるように、籠を花入の代名詞のように考えていることも理解していたつもりでした。なげいれという「草」の様式に、たてはな的「真」がおりたたまれていることを独自に感得し、みずから実践してきたことが川瀬さんの花の歴史的意義であり、そうした思想をあらわす器として、つまり「草」でありながら「真」に変容しうるものとして、たしかに籠ほどふさわしい器はないのでしょう(ここでいう「真」は唐物籠の「真」とはことなり、すなわちすでにある「真」ではなく、あるときあらわれる、なるものとしての「真」です)。

おそらく四桁に近い数の籠を手にしてきた川瀬さんが手もとにのこしてきたもの、そこからさらにえらばれた十数点を今回(昨年九月)撮影したのですが、むろんそれらは造形的にも、いわゆる味のよさにおいても、みごとな籠ばかりでした。しかし取材時の川瀬さんはそれにはほぼ無頓着で、籠のかたちはみえなくていい、とまでいうのでした。そして今回は花もそうでした。きえること、みえなくなることによりあらわれるもの。あるものではなく、あらわれるものとしての花をいけようとしていたのだと思います。S

In calligraphy, there is an expression 真行草 “shin-gyou-sou”, which means three styles: ‘shin’ 真 being square and formal, ‘gyou’ 行 being semi-formal, and ‘sou’ 草 being cursive and informal. The previous issue featured antique baskets (Karamono-kago), which represented flower baskets of that ‘shin’ type. The present issue, on the other hand, features those of ‘sou’ type, which include fish creels and wicker baskets for agriculture. From the outset, we had planned two issues to be devoted to baskets. I have known the Japanese flower arrangement artist Toshiro Kawase over two decades, interviewing him three hundred times (a natural consequence of being an editor of a monthly magazine to its long-standing regular contributor), so I thought I understood how important baskets were to Kawase, taking them as the symbol of ‘flower containers’ just as cherry blossoms symbolise flowers as a whole. The historical significance of Kawase’s flower arrangment lies in his unique practice based on his realisation that the ‘sou’ style of ‘Nageire’ incorporates the shin’ style of ‘Tatehana’. To Kawase there is no more appropriate containers than baskets as something that is ‘sou’ but can be transformed to ‘shin’. (This ‘shin’ differs from the ‘shin’ of antique baskets, something that is already there; it is something that manifests itself at some point, something that generates itself).

For this issue, a dozen baskets were photographed in September 2018, selected from the personal collection of Kawase, who have dealt with near a thousand of them. Those chosen baskets were wonderful both in their forms and in taste, but at their photoshoot, Kawase was indifferent to those aspects, and even explicitly said that the photos need not show their shapes. The same went for flowers this time. He was trying to arrange flowers, not as something that is there, but that manifest themselves even when they are (made) not seen. (S)

5|骨董と私

On My Antique Collection

古い工芸品をどうみるか、どう評価するかは、立場によってかわります。いまの日本では「美術史」「歴史学/考古学」「古美術」「茶の湯」「民芸」「骨董」「古道具」などのみかたがあり(かさなるところもありますが)、たとえば「美術史」的には国宝でも、「骨董」的には凡作ということはままあることです。よいことだと思います。いまおもしろいなと感じているのは「古道具」と「骨董/古美術」との差違で、後者(の両者の差違も興味ぶかいですが)は近現代にすでにあるていどの語誌的蓄積があるのにたいして、「古道具」概念は現在進行形で生成中の感があり、そこにはとうぜんこの時代、社会のなにごとかが反映されているはずなので、現代人のひとりとして、おもしろくないわけがないのです。

〈美術史の専門家は、時代の明白な作品を基準にして類例を集め、それぞれの特徴を分類し帰納的に編年を行い、様式論を展開する。骨董屋さんの頭の中にはその様式論がほぼ入っているわけだが、学説の記述でいちおう仕事が終わる学者研究者と違って、商売という行為のはじまりはその先にある。早い話が、典型的様式を踏んでいても売れないものは売れない。それを売れるようにするのは、店の主人の、そして店そのものが、脈々として持つ美意識ではないかと私は思う。(略)美意識の合わない店からはしぜんと足が遠のく。客は客でそれなりの「理想」を持っているからだ〉(杉村理)

この特集は奈良在住の収集家、杉村理さんの収集品を紹介しつつ、杉村さんの骨董随筆を掲載します。「美術史」と「骨董」の差(熱量差)がよくわかります。その差は「所有」の有無で説明されることが多いのですが、それだけでしょうか。S

The appreciation and the evaluation of antique crafts differ greatly, depending on who evaluates. In modern Japan, there are categories such as ‘art history’, ‘history or archaeology’ ‘antique’, ‘tea ceremony’, ‘mingei (Japanese folk craft)’ ‘curios’ and ‘bric-a-brac (furudogu)’, though some of them are difficult to separate. For instance, even if art historians evaluate an object as a national treasure, for a curio, it often happens, the object can be a mediocre work. I think that it is good to have such variations in judgment. At the moment, I am particularly interested in the difference between ‘bric-a-brac’ and ‘curios/antique’. The latter has already become a known term, whereas the formation of the concept of the former is still in the process of formation. It is inevitable that in this process, the concept is affected by the mentality of the epoch and the contemporary society, so it would never be boring as we all live in this same epoch.

‘When dealing with an unknown object, art historians gather dated examples with similarities, categorize them to make a timeline, and define their styles. Dealers also have to study the styles, but their task starts from thereon. Unlike the art historians whose task is complete once the categorization and the definition of the styles are made public, for the dealers that is where the business begins. Even if an object is typical of a style, not every one of them can be salable. I think the dealer himself and the aesthetics of the shop make an object salable. (…) I keep distance from the shops with aesthetics out of my taste. The customers have their ideals, each in their own way.’ (Osamu Sugimura)

The article introduces the collector, Osamu Sugimura in Nara, and his collection, and it is with his essay on antiques. A subtle difference (of enthusiasm towards objects) between ‘art history’ and ‘antique/curios’ is clarified in the essay. The difference is often explained by the matter of ownership but is it truely so? (S)

6|ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群 5

Fragments on Robert Coutelas 5

作家の堀江敏幸さんによる、フランスの画家ロベール・クートラス(一九三〇—八五)の紀行的評伝、第五回です。連載のこれまでをふりかえると─第一回は銀座の画廊でクートラス作品と出会ったこと、評伝を書くにいたるいきさつ、パリの墓地へ。第二回は画家の出生時と幼少期、とくに戦時下ドイツへ家族で移り、そこでみたことに思いをはせる。第三回はフランスのオーヴェルニュ地方へ。義父と暮した一〇代のうすぐらい日々。紡績工場づとめのかたわらはじめた木彫。第四回はクレルモン=フェランでひとり暮し、ロマネスク美術との出会い、石工修行、ブールジュ大聖堂の修復工事─そして今回は、ノルマンディー地方ルーアンへ。S

This is the fifth part of a biography of a French artist Robert Coutelas (1930─85) by a writer, Toshiyuki Horie. In his first instalment, the writer depicts his encounter with works of Coutelas for the first time in a gallery in Ginza, how he came to write this biography, and his visit to a cemetery in Paris. In the second, he recounts the artist’s birth and childhood, especially his time and experience in Germany during the War. The third looks at his days in Auvergne: his gloomy adolescence with his stepfather, and his initiation to woodcarving while working at a spinning mill. The fourth deals with the artist’s living on his own in Clermont-Ferrand, his encounter with Romanesque art, training in masonry, and his restoration work of the Bourges Cathedral. And this instalment shifts its focus to the artist’s days in Rouen, Normandy. (S)

7|名物とはなにか

What is Renowned Objects (Meibutsu) in tea utensils?

名物とは由緒ある茶道具のこと。利休の時代より古くからある名品を「大名物」、利休時代のものを「名物」、小堀遠州由来のものを「中興名物」とよびますが、その分類は大名茶人で大収集家でもあった松平不昧(一七五一—一八一八)によります。その不昧による『古今名物類聚』や、近代の『大正名器鑑』などの「名物集」、そして遠州、不昧、加賀前田家や仙台伊達家といった茶数寄の大名家等の「蔵帳」(蔵品目録)所載であることも、名物のひとつの条件のようです。ただし厳密な定義はなく、取材した茶人の木村宗慎さんによれば「名物はふえてゆく」とのこと。

今回撮影したのは加賀前田家伝来の古瀬戸耳付茶入、一点のみです。前田家の蔵帳にあり、『古今名物類聚』と『大正名器鑑』にも載るまぎれもない名物です。名物にふさわしく、外箱、内箱、挽家(茶入をおさめる容器)、仕服、四方盆(茶入をのせる)、同作所載の名物集など、この茶入の由緒と価値をしめすそれぞれがしっかりとそなわり(ほかに風呂敷や古い紐などもあります)、このページ数になりました。

「名物」の記事、茶道具の記事なのでこうしました。意味あることだと思います。しかしいっぽうで、やはり茶の湯の記事はむつかしい、つくる動機をみいだしにくい、とあらためて感じました。〈『工芸青花』は、この時代の人々がなにを感じて、なにを考えたかを、(後世に)つたえるための本〉と公言しているのですが、茶の湯は過去に完成したすぐれた文化であり、新味の余地も必要もないように思うからです。名物はすでに評価されたものであり、それを否定するのならともかく(とくに否定したいとは思いません)、過去の評価をなぞっても屋上屋を架すだけです。

そんなことを木村さんに話して、反論を書いてもらいました。S

‘Meibutsu (renowned objects)’ are the tea utensils with history. The ones older than Rikyu are called ‘O meibutsu (great renowned objects)’ and the ones in the taste of Enshu Kobori are called ‘Chuko Meibutsu’. Great tea master and a grand collector, Fumai Matsudaira (1751─1818) coined the categories. There are catalogues of Meibutsu, such as Traditional Renowned Objects Collection by Fumai, and Renowned Objects Catalogue in Taisho Period to define. Also, objects are said to be ‘renowned’ when registered in the inventories of the great feudal lords such as Maeda family in Kaga or Date family in Sendai, who enjoyed the tea ceremony as tradition. However, according to Soshin Kimura, ‘Meibutsu is still increasing’.

For the article, I photographed the tea container made of the ancient Seto ceramic with little handle, said to be owned by Maeda family in Kaga. It is the authentic Meibutsu which is registered in the inventory of Maeda family, and in the catalogues, Traditional Renowned Objects Collection by Fumai, and Renowned Objects Catalogue in Taisho Period. Appropriate to the status of Meibutsu, the tea container came with everything to show its history and value, i.e. the outer box, the inner box, the wooden container to house the Meibutsu, the cloth to wrap everything, the square tray to put the container, the catalogues which register this Meibutsu (and a large wrapping cloth and an old woven cord), hence, many pages are devoted.

This is typical of the article on Meibutsu and tea utensils. It is meaningful in a way but at the same time, I feel difficulty in making articles on tea utensils. I do not quite see the significance. I always say that ‘Kogei Seika is the book to convey the feeling and thought of the contemporary to the posterity’. I do understand that the tea ceremony is a great culture but it has already accomplished to perfection in the past, and I feel that there is nothing to add. Meibutsu is evaluated already and unless you want to dispute over the evaluation, which is certainly not my intention, revising the evaluation of the past is pointless.

To such opinion of mine, Soshin Kimura writes refutations in the article. (S)