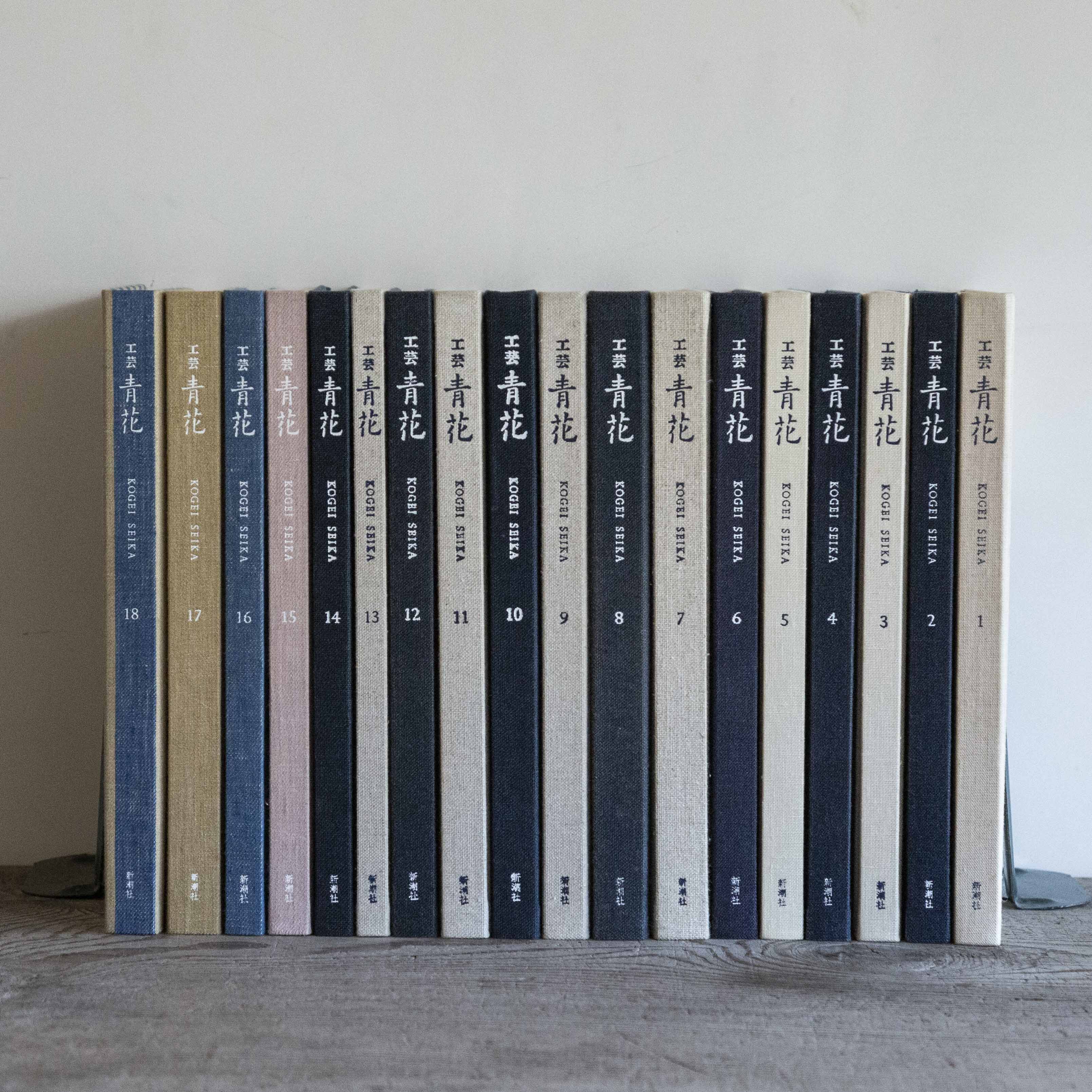

『工芸青花』10号

■2018年7月30日刊

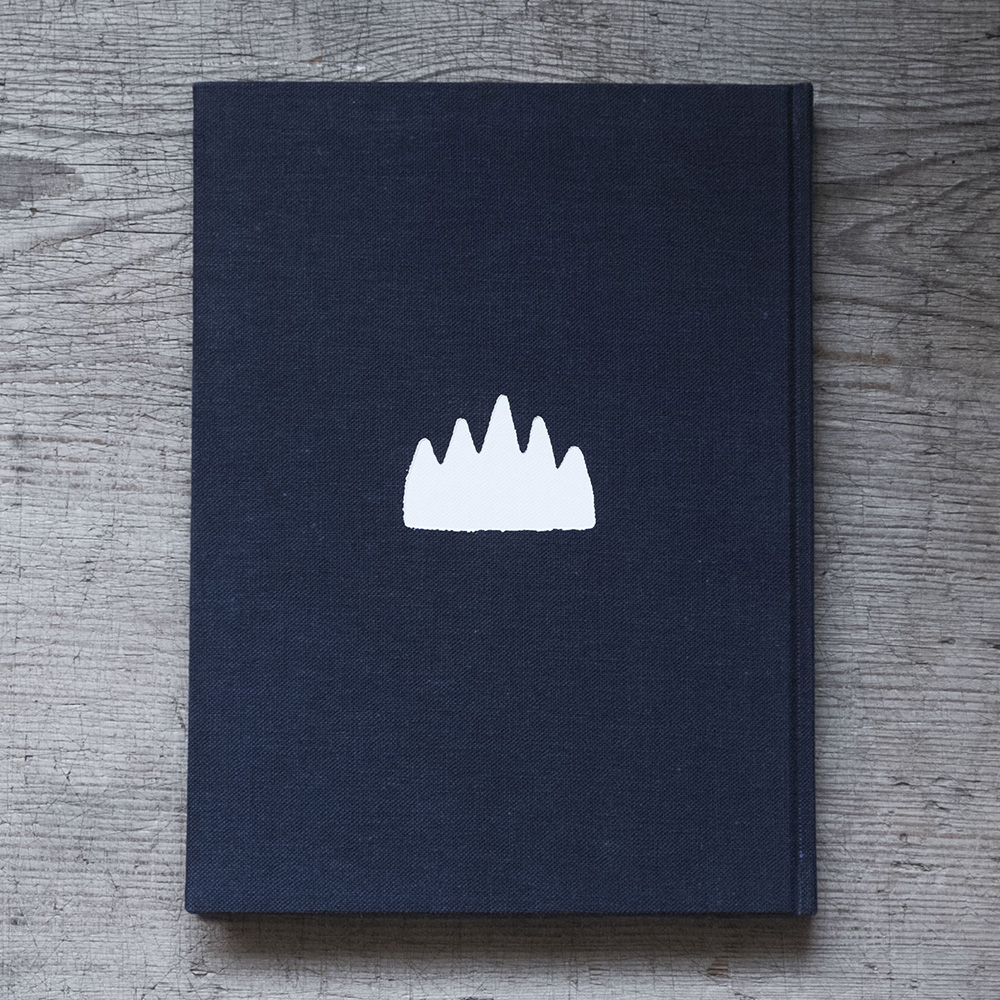

■A4判|麻布張り上製本|見返し和紙(楮紙)

■カラー184頁|古布(西洋更紗)を貼付したページあり

■限定1200部|12,000円+税

■御購入はこちらから

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=242

Kogei Seika vol.10

■Published in 2018 by Shinchosha, Tokyo

■A4 in size, linen cloth coverd book with endpaper made of Japanese paper (kozo)

■184 pages of colour plates, with a piece of toile de jouy on frontispage

■Each chapter is accompanied by an English summary

■Limited edition of 1200

■12,000 yen (excluding tax)

■To purchase please click

https://shop.kogei-seika.jp/products/detail.php?product_id=242

目次 Contents

1 川瀬敏郎の花 唐物籠

Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase: Flowers in Chinese Antique Baskets

・真と自由 片柳草生

2 坂田和實の眼 酒袋

The Eye of Kazumi Sakata: Sake bags

・錆びたナイフ 高木孝

・坂田さんの優しさ 高木崇雄

3 スイスのロマネスク シオンのノートルダム・ド・ヴァレール聖堂

Romanesque Art in Switzerland, Basilique Notre-Dame de Valère

・家具と夕日 金沢百枝

・ハイジの国の中世 小澤実

4 座辺の李朝

To Cherish Beside Me:

・李朝・蒐集・近代 大塚麻央

5 黒田泰蔵 白磁と轆轤

Taizo Kuroda: White Porcelain and a Potter’s Wheel

・円筒と彼岸 赤木明登

6 ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群 4

Fragments on Robert Coutelas 4

・石工への道 堀江敏幸

7 骨董と私

On My Antique Collection

・子供的なもの 藤田康城

8 意中の美術館 6

Museums on My Mind 6

・ビルバオ・グッゲンハイム美術館の巻 中村好文

世界の布

精華抄

1|川瀬敏郎の花 唐物籠

Ikebana by Toshiro Kawase: Flowers in Chinese Antique Baskets

花人の川瀬敏郎さん(一九四八年生れ)の花、今回の主題は唐物籠です。唐物籠とは室町期より将来された中国の花籠で、明清の作を本歌として、日本でも写しがつくられました。牡丹籠、耳付籠、手付籠などがあり、編みぶりは精巧で、籠花入のなかでは(真行草の)真の器とされます。すなわち場とのとりあわせも大事で、このたびは京町家を代表する杉本家住宅(一八七〇年)の座敷でいけています。

いけているあいだ、川瀬さんがくりかえし話していたのは唐物籠の花の「自由」ということでした。「真」であるがゆえに、こころという私的なもの、不安定なものが入りこむ余地がなく、無心に、無私に、近づくことができるというのです。S

The theme of Ikebana in this issue, by Toshiro Kawase born in 1948, is Chinese antique baskets (Karamono-kago). They are baskets originally introduced from Ming dynasty China to Japan in the Muromachi period (1336─1573), inspiring many types of Japanese versions, including peony baskets, eared baskets, and baskets with a handle. Because their weave is so exquisite, they are said to be the finest of the kind. Accordingly, those baskets should be placed in special settings, for which Kawase has chosen the zashiki (Japanese-style tatami room) of the Sugimotos’ house (1870), one of the best traditional Machiya buildings in Kyoto.

While arranging flowers, Kawase repeatedly mentioned the word ‘freedom’ of the flowers in those antique baskets. Since they are of the finest quality, there is no room for personal feelings, or something unstable, to intervene, and he felt as though he was entering the state of selflessness and innocence. (S)

2|坂田和實の眼 酒袋

The Eye of Kazumi Sakata: Sake bags

東京目白にある古道具坂田の坂田和實さん(一九四五年生れ)は、千葉県長南町にある美術館 as it isの館主でもあります。二〇一五年から翌年にかけての展示で、壁にぐるりと貼られていたのが四、五十枚の酒袋でした。明治大正ごろのもので、酒や醤油を醸造するさいにを入れて圧搾するための袋です。くりかえしつかってやぶれたところにツギをあてています。前章(唐物籠の花)では無心や無私という語が願望として語られるのですが、これらの袋はすでにそこに達しているようにみえます。すでに「花」のようです。

酒袋とは直接関係ないのですが、坂田論を二本掲載しました。古美術栗八の高木孝さんの文章は、二〇一二年に渋谷の松濤美術館で坂田和實展がひらかれたときに書かれたブログの再録です。工藝風向の高木崇雄さんの文は書き下ろしです。S

Kazumi Sakata born in 1945, the owner of ‘Antique shop Sakata’ in Mejiro, Tokyo, is also the owner of the museum ‘as it is’ in Chonan, Chiba. As part of its ‘permanent’ exhibition from 2015 to 2016, forty to fifty ‘sake’ bags were displayed on the wall. Those were from the Meiji and Taisho periods (1868─1926) and were used in the production process of sake (Japanese rice wine) or soy sauce: main fermenting mash were pressed and filtered in those bags. Through repeated use, those bags become tattered, but they were patched and re-used. Just as the selfless innocence of flowers in the Chinese antique baskets in the preceding chapter, these ‘sake’ bags seemed to have reached such a state. To me they are like ‘flowers’.

This chapter also includes two articles on Kazumi Sakata, if not directly related to ‘sake’ bags. One is by Takashi Takagi, the owner of ‘Antique Kurihachi’ in Roppongi, Tokyo, taken from his blog entry about the exhibition of Sakata held in Shoto Museum in 2012. The other is newly written by Takao Takaki, the owner of Japanese craft shop ‘foucault++’ in Fukuoka. (S)

3|スイスのロマネスク シオンのノートルダム・ド・ヴァレール聖堂

Romanesque Art in Switzerland, Basilique Notre-Dame de Valère

中世ヨーロッパのロマネスク聖堂の取材をはじめて十数年になりますが(そのほとんどが美術史家の金沢百枝さん、歴史家の小澤実さんとともに本や記事をつくるための旅です)、スイスははじめてです。ドイツ語、イタリア語、フランス語地域の順に車でまわりました。想像よりもずっと山国でした。

今号は南西部、(フランス語地域の)シオンの岩山のうえにあるノートルダム・ド・ヴァレール聖堂をたずねます(となりの岩山のうえにもロマネスク時代の古城址があります)。聖堂の建造はロマネスク期(一二世紀前半)ですが、ゴシック期(一三—一四世紀)に大きく改築されています。ここでめずらしいのは、聖堂内におかれていた櫃など、中世の木の家具が多くのこっていることです。S

It has been more than a decade since I began travelling around Europe to visit Romanesque churches (almost every trip was made to produce books and articles with Momo Kanazawa, an art historian, and Minoru Ozawa, a historian), but this was my first visit to Switzerland. We drove through the German-speaking, Italian-speaking, and French-speaking regions. The country was much more mountainous than I had imagined.

In this issue, the article is on Sion, in the south west part of Switzerland, the French-speaking region. There we visited the basilica of Notre-Dame de Valère on top of a rock mountain. (There was another rock mountain next to it, and on top of it, there is a ruin of a Romanesque castle.) The church was built in the first half of the twelfth century, but the building was largely renovated during the thirteenth to fourteenth centuries. We were thrilled to find the rare examples of medieval wooden furniture, such as the chests used in the church. (S)

4|座辺の李朝

To Cherish Beside Me:

The Private Collection of Antique Ceramics from Joseon Dynasty

『座辺の李朝』という本は、昭和四六年(一九七一)に李朝陶磁の収集家、中川竹治(一八九九—一九九四)が七〇〇部限定の私家版として刊行した自身のコレクション図録です。約四〇年の収集歴から一〇〇点をえらび、それぞれに短文を附しています。

〈その頃、古陶磁としての李朝はまだ歴史が浅く、国立美術館や上層階級の人達に認められないのは勿論、業界に於いてさへ外道扱ひされてゐたのである。それで時には僅か三~五円で楽しめる品が手に這入ったのだから若いサラリーマンにとって李朝は格好の道楽の対象であった〉(『座辺の李朝』「序」より)

もちろんその後李朝の評価はたかまり、『座辺の李朝』も李朝愛好者必携、垂涎の書として古書価は高騰しました(二〇一五年に青月社から復刻版が刊行されています)。中川コレクションは生前から市場にでていますが、『座辺の李朝』所載品はとうぜんのごとく人気です。

今回はそのうちの七点を撮影、掲載しています。いずれも京都嵐山にある「ミュージアム李朝」の蔵品です。S

The book To Cherish Beside Me: The Private Collection of Antique Ceramics from the Joseon Dynasty by Takeji Nakagawa (1899─1994), a collector of ceramics of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea, was published in 1971 as a catalogue of his own collection. A limited edition of 700 copies was produced for private circulation. For this book he chose one hundred ceramics from his collection built up over around forty years and wrote a short essay for each item.

In the introduction of the book, he recalls his old days: ‘At the time, not many people collected antique ceramics from the Joseon Dynasty. They were appreciated neither by curators of National Museums and upper-class people, nor by antique dealers who considered them to be unworthy of their attention. So, I could acquire terrific items, sometimes at around three to five yens, prices well within the reach of a young white-collar like myself. It was such a joy to collect ceramics of the Joseon Dynasty in those days.’

As we all know, the Joseon porcelain came to be highly appreciated, and at the same time, the price of his book itself, craved by collectors of the ceramics as an indispensable reference, dramatically soared in the antiquarian book market (the reprinted edition was published in 2015 from Seigetsusha). The collection of Nakagawa was out in the antique market before his death and the ones discussed in the book are inevitably popular.

Seven ceramics from the book, all of which are from the Museum Richo, in Arashiyama, Kyoto, appear in this chapter. (S)

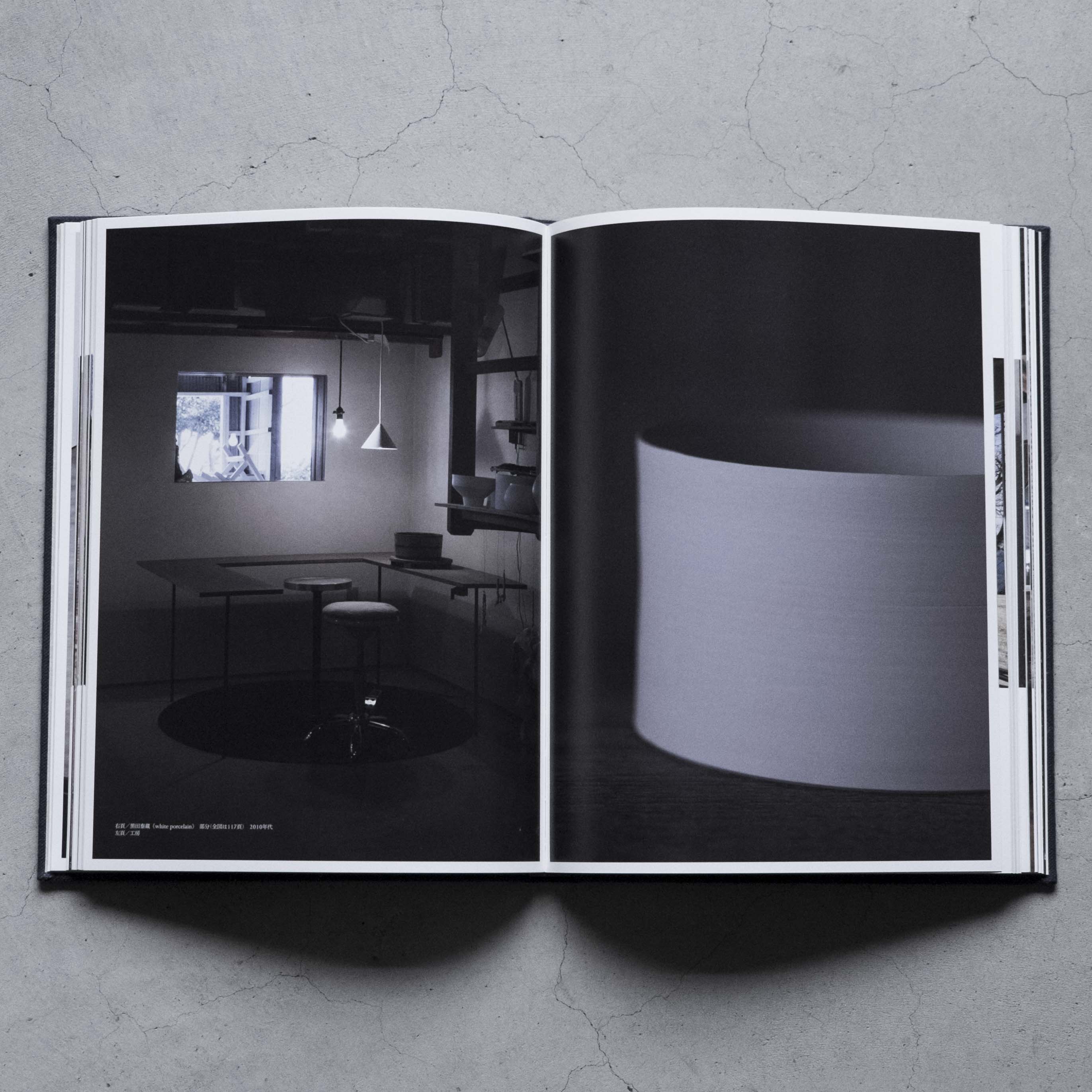

5|黒田泰蔵 白磁と轆轤

Taizo Kuroda: White Porcelain and a Potter’s Wheel

陶芸家の黒田泰蔵さんは一九四六年滋賀県生れ、二〇歳で渡仏し、パリの日本食レストランではたらいていたときに客としておとずれた益子の陶芸家島岡達三と出会い、その縁でカナダの陶芸家ゲータン・ボーダンに師事、やきものをはじめます(一九六七年)。〈「これを一生やるかもしれない」/僕は轆轤に夢中になっていた〉(『黒田泰蔵 白磁へ』)

一九八一年に帰国、伊豆松崎に築窯し、白地に赤、黄、緑で彩文した器で人気を博すのですが、本人は〈これは嘘だ、という思いがいつもあった〉(同)と当時をふりかえっています。〈本当は何をやりたいのだろう。心の中で何万遍も繰り返したはずの自問をさらに繰り返し、若い時から白磁が好きだったと確信した〉。九一年、あらたに伊東に制作の場を移し、九二年以降は白磁のみつくりつづけています。

孤高という形容がおさまる数すくない工芸家のひとりであり、自覚的に器の彫刻化(彫刻の器化ではなく)をはたしたさきがけであり、国内外ですでに評価のさだまった大家でもあるのですが、黒田作品の核心はいまだ解明されていない、と輪島の塗師で工芸論の書き手でもある赤木明登さんは考えていて、今回、伊東をたずね、黒田論を執筆していただきました。S

The book To Cherish Beside Me: The Private Collection of Antique Ceramics from the Joseon Dynasty by Takeji Nakagawa (1899─1994), a collector of ceramics of the Joseon Dynasty of Korea, was published in 1971 as a catalogue of his own collection. A limited edition of 700 copies was produced for private circulation. For this book he chose one hundred ceramics from his collection built up over around forty years and wrote a short essay for each item.

Taizo Kuroda is a ceramic artist born in Shiga in 1946. At the age of twenty, he went to Paris. While working in a Japanese restaurant, he met Tatsuzo Shimaoka, a famous potter from Mashiko, who gave him a chance to train under Gaétan Beaudin, a ceramic artist from Canada. Thus his carrier as a potter began in 1967. In his book Taizo Kuroda: Towards White Ceramics, he recalls those days: ‘I thought I might as well end up devoting my life to it’; ‘I was obsessed with “the potter’s wheel”’.

In 1981, he returned to Japan and settled in Matsuzaki on the west coast of Izu Peninsula. His white ceramics painted with red, yellow, and green became popular, but he recollects that time and writes: ‘I was always wondering “There is something wrong, even false about the whole thing”’; ‘What is it that I really want to do? I questioned myself repeatedly, thousands and thousands of times, and in the end, I was absolutely sure that I loved white porcelains from the beginning.’ In 1991, he moved his studio to Ito of the peninsula and since 1992, he has concentrated on white porcelains.

He is one of the few craftsmen whose artistic visions truly set themselves apart from others, and is a pioneer of transforming ceramics into sculpture (not vice versa). He is widely renowned in and outside Japan, but Akito Akagi, an artist of Japanese lacquerware and a writer of crafts in Japan, is of the view that Kuroda’s artistic essence has yet been fully explored. In this chapter, Akagi visits Ito and comes up with his new views on Kuroda. (S)

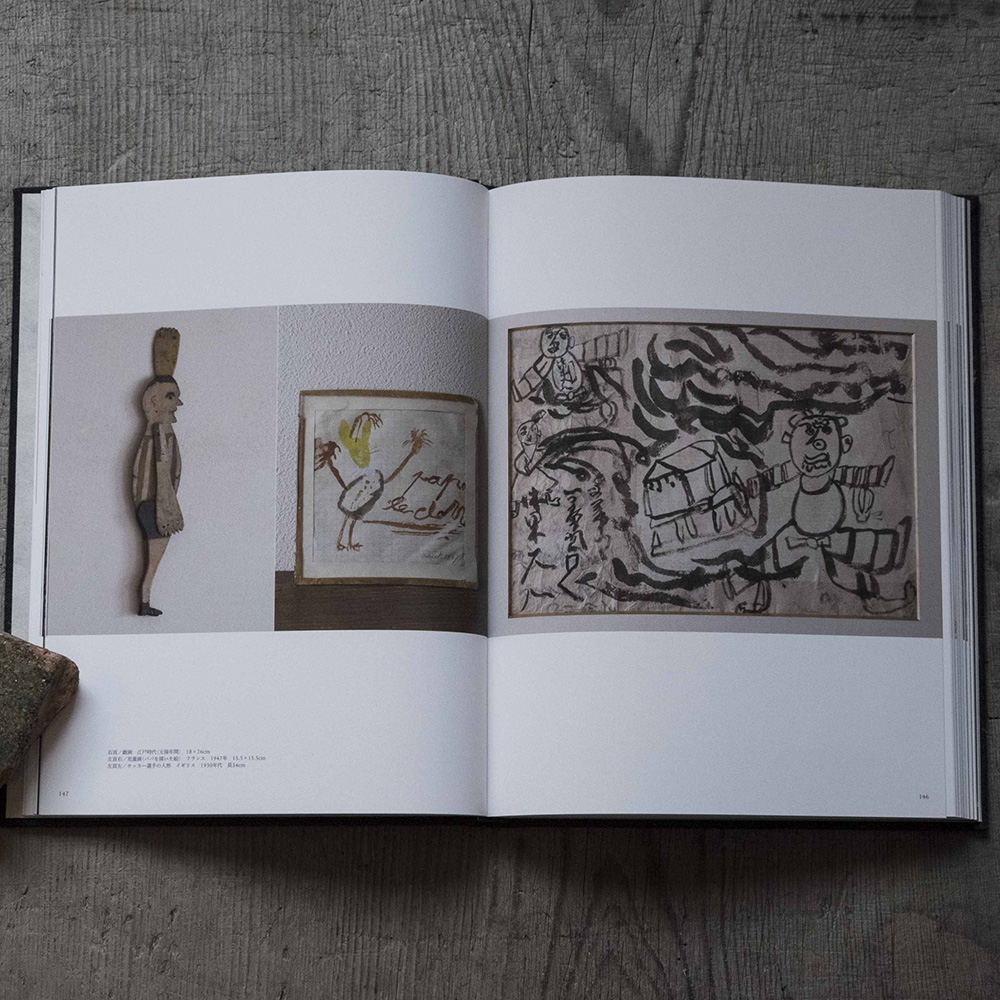

6|ロベール・クートラスをめぐる断章群 4

Fragments on Robert Coutelas 4

作家の堀江敏幸さんによる、フランスの画家ロベール・クートラス(一九三〇—八五)の評伝です。

前号は画家が一〇代をすごしたオーヴェルニュ地方ティエールをたずねたときの話でした。そこでは義父とふたり暮しで、ともに紡績工場ではたらきながら、クートラスは古民具収集の趣味をもち、自身も木彫をこころみるようになるのですが、父親の無理解に直面し、二度も自殺をはかります。

今号はそんな義父のもとをでて、おなじオーヴェルニュ地方クレルモン=フェランでひとり暮しをはじめたころの話です。S

This is the fourth part of a biography of a French artist Robert Coutelas (1930─85) by a writer, Toshiyuki Horie.

The previous issue was on Horie’s visit to Thiers in Auvergne where the painter spent his youth. He lived there with his stepfather. While working in a spinning mill, he collected old folkcrafts and began making wood sculptures himself. However, his stepfather’s denial of his passion in Art led him to two suicide attempts.

In this issue, the story moved on to the time when Coutelas left his stepfather’s house and started to live alone in Clermont-Ferrand, also in Auvergne. (S)

7|骨董と私

On My Antique Collection

シアターカンパニー「アリカ」の主宰者・演出家である藤田康城さん(一九六二年生れ)の骨董コレクションを紹介します。

〈すぐれた演劇を見て心が動かされるように、古いものを通じて、人間という存在のドラマを夢想すること〉(藤田康城)

きっかけは、知りあいの編集者が藤田家をたずねたときの印象を語った言葉でした。「部屋には本と、古いものがたくさんある。骨董のことはよくわからないけれど、人のかたちをしたものが多かった。関心がない自分が気づくくらいだからね」

藤田家をたずねたときにそのことをいうと(たしかに知人のいうとおりでした)、藤田さんは気づいていませんでした。記事のテーマは「骨董・身体・子供」です。〈私たちARICAの演劇は、身体行為を中心に、奇妙な道具や装置を駆使して、その行為を拡大、変容、展開させていく舞台だ。それは、少なからず遊戯的で、無心に遊びに向かう幼い子供の生命力と共通すると考えている〉(同)

「骨董と私」特集では、骨董とはなにかという問いのこたえを拡張し、更新できたらと思っています。S

This chapter is on the antique collection of Yasuki Fujita (born in 1962), a director of the Theater Company ARICA. For Fujita, ‘To collect antiques is to dream the drama of human existence through those objects. For me, it is like being moved by a performance in a theatre.’

A chat with an editor led to this chapter. Upon his visit to the Fujita’s, he noticed that ‘the room was full of books and antique objects’. ‘I do not know much about the antiques but most of them were figures. They were conspicuous even to a non-antique lover like me.’

When I visited, his place was exactly as my friend described. When I told him that, surprisingly, Fujita was not particularly aware of that. The theme of the article is ‘Antique, Body, and Children’.

He writes, ‘We, ARICA, value most the physical performance. We value the physicality of an actor and it expand, transform and develop dramatically, using peculiar objects and extraordinary stage sets. Our performance is in a way playful and it has something in common with the vivacity of infants innocently absorbed in their play.’

In this article, I would like him to engage with the question, ‘Why do we collect antiques?’, and expand and renew answers to it. (S)

8|意中の美術館 6

Museums on My Mind 6

建築家の中村好文さんが意中の美術館をたずねる旅、今回はスペイン北部バスク地方ビルバオにあるグッゲンハイム美術館です。開館は一九九七年、設計はフランク・ゲーリー(一九二九年生れ)。マーク・ロスコ、ジャクソン・ポロック、サム・フランシス、アニッシュ・カプーア、ジェフ・クーンズ、ルイーズ・ブルジョア等々の作を常設でみることができます。アメリカのグッゲンハイム財団は現代美術の収集で知られ、ビルバオのほかニューヨーク(一九五九年)とヴェネツィア(一九七九年)にも美術館があります。

この〈丸めて放り投げた銀紙の塊〉(中村さん)のような外観のビルバオ・グッゲンハイムと、「普通の住宅」を標榜する建築家である中村さんとの相性はどうなんだろう、と取材するまえは思っていたのですが、いまでは「なるほど、たしかに」と得心がゆきました。また、ここには中村さんの「意中の彫刻家」であるリチャード・セラ(一九三九年生れ)の大作もあり、そちらについても読みごたえがあります。S

The architect, Yoshifumi Nakamura’s visit to his favourite museums continues. In this issue, we went to the Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, in the region of Basque, north of Spain. The museum opened in 1997, designed by Frank Gehry, born in 1929. Its permanent collection exhibits the art works by Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, Sam Francis, Anish Kapoor, Jeff Koons, and Louise Bourgeois. The Guggenheim Foundation in U.S. is renowned for their collection of modern art and runs museums in New York City (built in 1959) and in Venice (built in 1979).

Before our visit, I had my doubts about the combination of the architect renowned for building ‘ordinary houses’ and the museum in the shape of ‘the scrunched up aluminium foil’ (description by Nakamura), but now I am convinced why he chose it. The museum exhibits the monumental piece by Richard Serra, born in 1979, one of the favourite sculptors of Nakamura. The article must be rewarding to the reader in that aspect as well. (S)